This is the hottest topic in coastal restoration. Learn more about this issue and make a decision for yourself.

Quick Note

I wrote this article in May of 2013. Since then, now in August 2017, my opinion on river water has changed drastically.

I still believe dredging works and we should dredge our marsh back. No doubt!

But I share my observations since then, fishing across Louisiana's coast in a new article. CLICK HERE to read it.

How Should We Save Louisiana's Dying Coast?

I will briefly go over the events leading to our present day scenario and will then touch on the controversial issue of dredging versus diverting. I will not go in-depth as this article is meant as a quick reference for anyone unaware of this important discussion.

At the end of the day, this article is really only an opinion based on my own observations.

It will be on you to do your research and formulate your own opinion.

Going Back in Time

Anybody that has visited the Mississippi River can readily tell you that she is indeed "mighty". Her gargantuan and powerful waters have forever changed the American landscape.

No area is impacted more than the estuary at the end of her journey to the Gulf of America. I try to describe my stomping grounds by using the word "vast".

It really is.

I have taken fishermen from all over the world into our marshes. They just can't believe how big and remote it is.

How did this come to be? We have the Mighty Mississippi to thank.

Is it really any surprise that Native Americans would worship this great body of water?

A quick look at a map of Louisiana coast will reveal where the river once flowed, dumping sediment and building land. Bodies of water like Bayou LaLoutre in Hopedale and Oak River in Delacroix are readily obvious.

These areas were built as the river would flood during the springtime and subsequently cover the area in sediment-laden freshwater.

Over a period of thousands of years the land mass we stand on today was built.

The Influence of Man

It wasn't long before colonists from Europe started settling the Americas and eventually moved onto the Mississippi. Many found it highly rewarding to farm alongside her banks and reap the bounties of this nutrient-rich river.

Interests led from one thing to another and some found it hard to cope with the flooding of the Mississippi every spring. She was also dangerous in the aspect that she could change course at any time, wiping out tracts of land.

Man's solution was to build levees and hold the Mississippi in what is her present day route. Through miraculous feats of engineering we have constrained her and are able to bleed her to safe levels whenever she rises too high.

This is life in the Mississippi Delta.

We have also built locks, padded her shorelines to prevent erosion and many other things that have changed the characteristics of the Mississippi and her land-building capabilities, all upstream of Louisiana.

The Mississippi River does not carry the same amount of sediment as she used to.

Consequences

Though most of man's efforts to subdue the Mississippi River were started with good intentions there have been consequences.

For starters, the Mississippi River was cut off from the wetlands she nurtured into existence. Without them being flooded annually there was no way they could be rebuilt with additional sediment.

More Damage

In a bid to improve the Port of New Orleans and introduce new jobs to St. Bernard Parish, the Army Corps of Engineers embarked on one of its worst blunders.

They expedited the death sentence of the freshwater marsh (now cutoff from the Mississippi's nurturing spring floods via levees) by building the Mississippi River Gulf Outlet, or MRGO. The idea was to create a shortcut for ships steaming towards the Port of New Orleans.

But the gigantic canal didn't prove viable, with fewer than 700 ships a year using it. At a cost of $10,000 per ship to maintain the MRGO, it was quickly deemed a failure.

It destroyed untold acres of marsh and introduced saltwater into an area that was previously fresh.

Further erosion from the construction of unneeded canals just worsened the issue. It's my guess that Hopedale and Delacroix once looked like what Bayou Segnette looks like today. That's what the old timers say as well.

Adaptation

Fishermen quickly adapted and found the saltwater marsh to be hardy and resistant to the surges of hurricanes. This provided more habitat for saltwater species like speckled trout, tarpon, shrimp, oysters and crabs. We already had an incredible fishery, this change in the ecosystem boosted that.

In present day Louisiana we have some of the best fishing in the world. It's indisputable.

Depending where you are in Florida, an angler can only keep a mere four to six speckled trout a day.

There is a similar limit in North Carolina and Texas does better with a ten trout per angler limit. They all have slot sizes, too!

In Louisiana, we keep 25 per angler with no slot size. This is due to our massive estuary that provides a spawning ground for all of these trout.

It isn't just trout!

It's also shrimp, redfish, oysters and crabs. Even Maryland, famous for her blue crabs, has to fall back on Louisiana to supplement her seafood industry. Here are a few pictures to demonstrate our awesome catches.

8,000 pounds of shrimp caught in a night

It isn't uncommon to catch limits of trout on a regular basis.

Present Day Scenario

In 1991 the Caernarvon Diversion was created in an effort to benefit the oyster industry and somewhat emulate what the Mississippi used to do years ago. Located in Caernarvon, Louisiana, the diversion is basically a giant sluice gate siphoning river water off from the Mississippi.

Yes, the oysters got bigger because they had more organic detritus to filter from the water.

However, the diversion actually harmed the surrounding marsh more than if it had never been built in the first place.

How big is this diversion? At max output it churns roughly 8,000 cubic feet per second of water into the Delacroix area.

It does not effectively replicate what the Mighty Mississippi used to do.

There is little sediment and it has instead created freshwater marsh that is not nearly as resistant to hurricanes as saltwater marsh.

Despite the best efforts by our government to do something worthwhile they once again made the issue worse.

In the wake of Hurricane Katrina and other storms we found that the freshwater marsh built by the Caernarvon Diversion was destroyed and left us with less land mass than what we had before.

In 2010 the diversion was opened up all the way in order to push the BP oil away from the Delacroix marsh. The attempt was futile as it killed oyster beds anyways.

Unacceptable Future

Now our problem has been compounded in that the Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority (CPRA) wants to build a larger diversion at nearby Braithwaite, this one capable of putting out 250,000 cfs of water.

That was not a typo! You read it right.

That is a quarter million cubic feet of water per second flowing into our saltwater marsh. If Caernarvon did that much damage what would a diversion of that magnitude do at Braithwaite?

Left in the hands of our government, it would destroy the marsh.

But it gets worse. If the marsh is destroyed then everything else will follow. It would be a devastating chain reaction that would cause Louisiana culture to become extinct.

If the oysters are gone, so are the oyster restaurants with everything in between from the oyster fishermen to the shipping and processing industries.

With no crabs and no shrimp to sustain our seafood culture then we could easily see restaurants, bars and other venues breaking down in New Orleans. People would lose their jobs and we would lose our culture.

Vital habitat for pelicans, terns and sea gulls would disappear. Untold environmental atrocities could occur.

We are told that this new diversion would be a "sediment" diversion, the delineating difference from Caernarvon. However, it is the freshwater that will destroy the fisheries. When asked what kind of sediment to water ratio we could expect to see, we were told "hopefully 1:1".

My biggest problem with this whole idea is that we are trusting the government to get it right this time despite spending decades and billions of dollars screwing it up.

The people in our government are not fishermen with a vested interest in the survival of their livelihood.

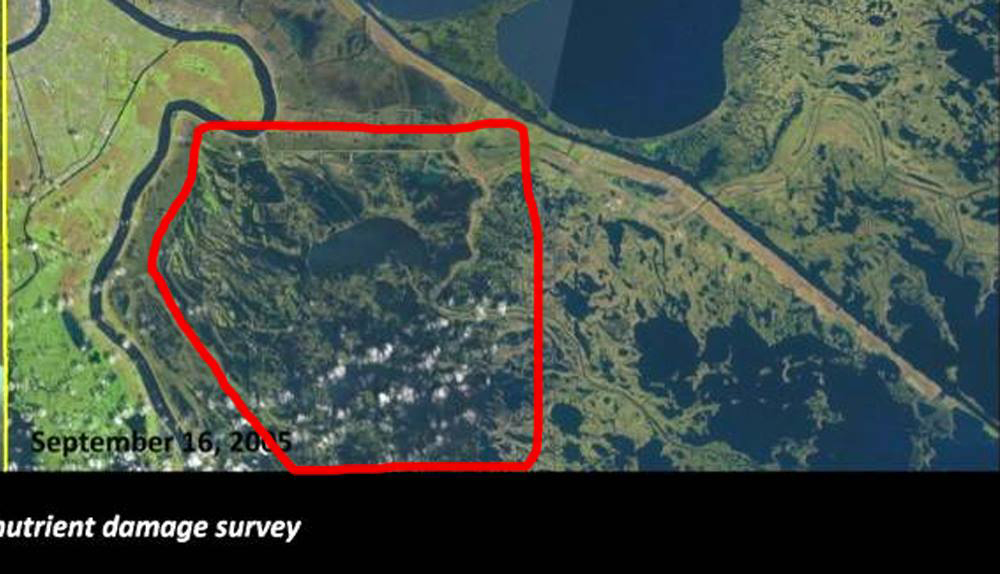

These pictures accurately show what a freshwater diversion will do to a saltwater marsh!

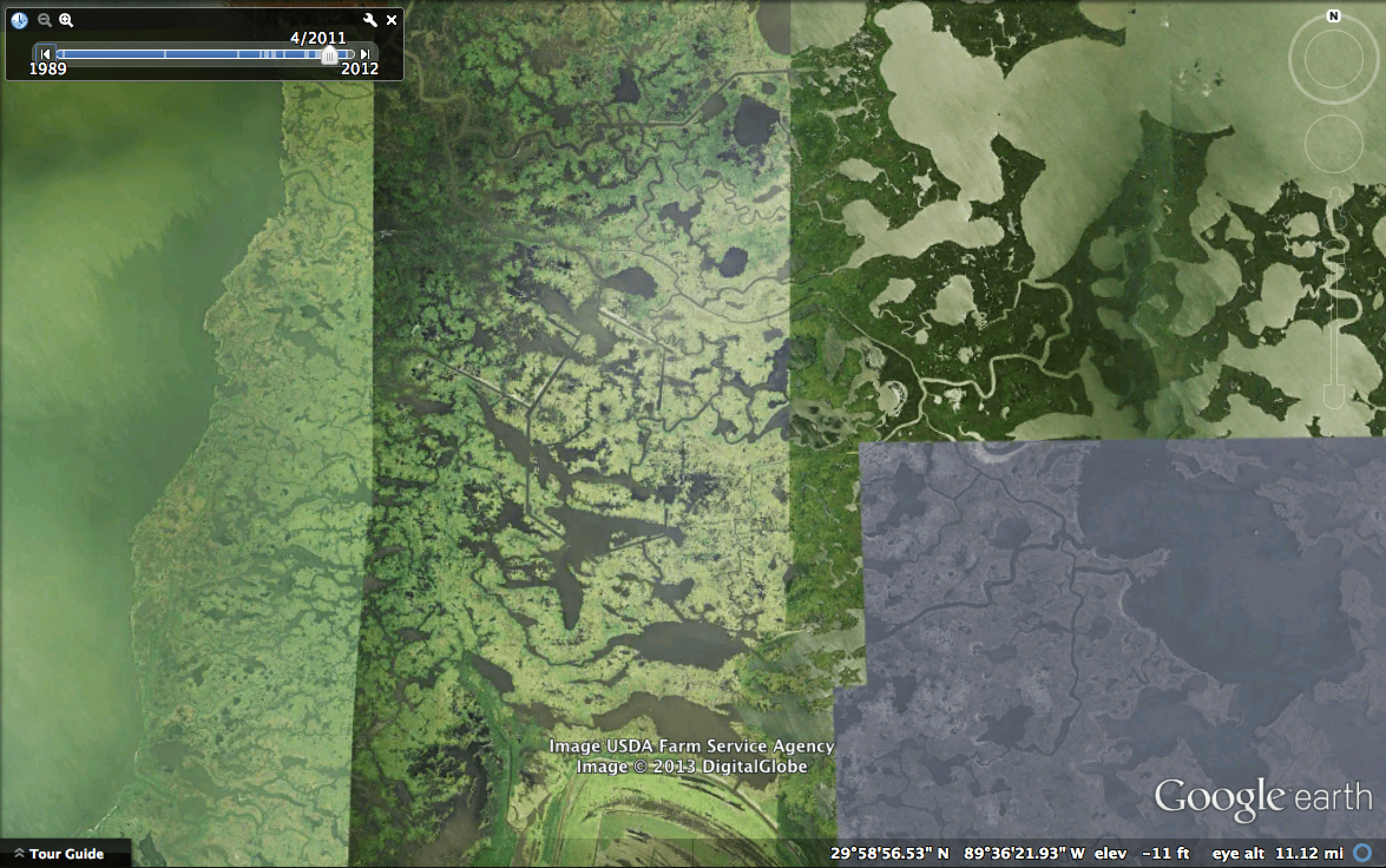

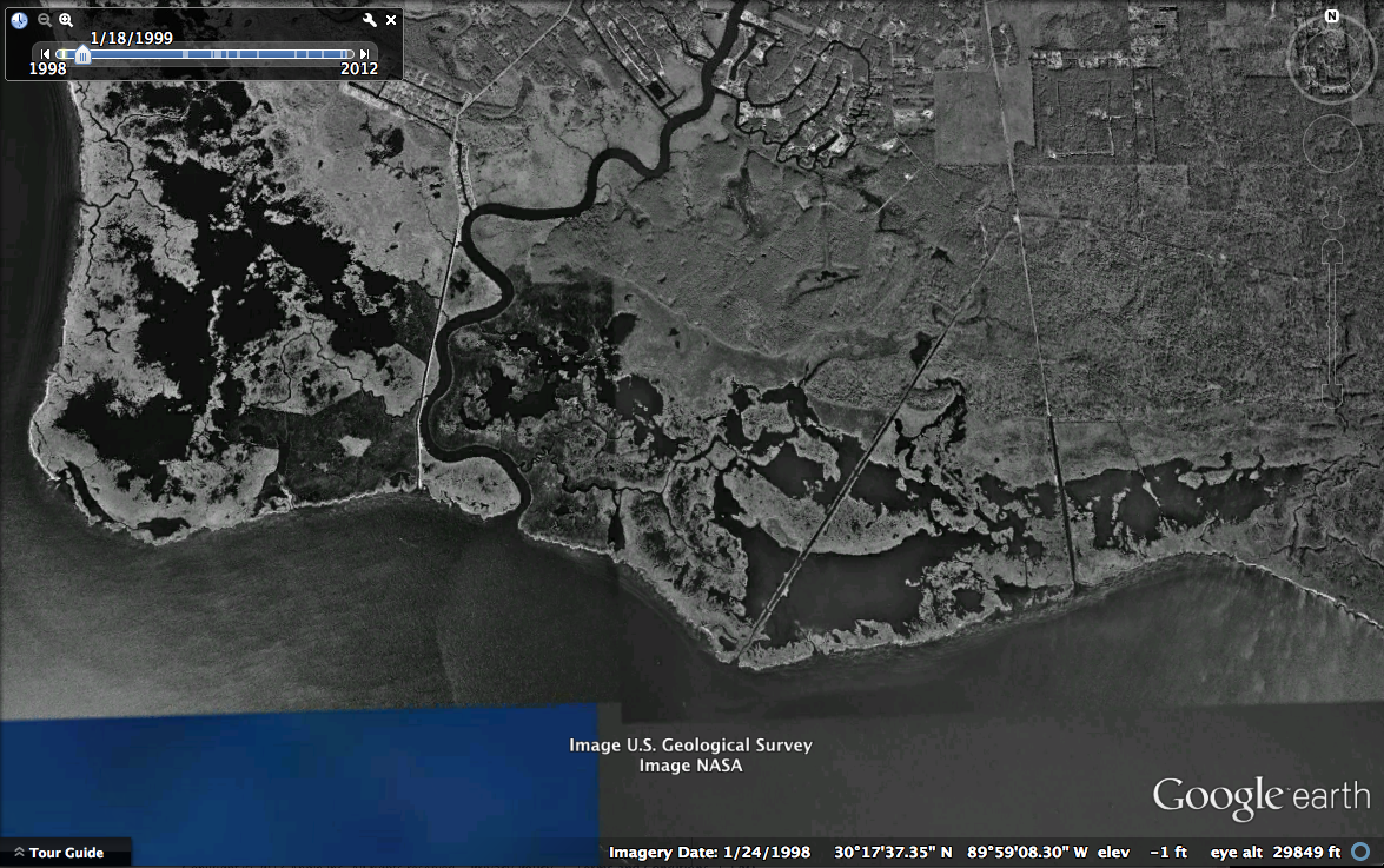

Now compare Delacroix against the Biloxi Marsh.

Click to Enlarge - Biloxi Marsh 1998

Click to Enlarge - Biloxi Marsh 2011

The difference between the Biloxi Marsh and the Delacroix marsh is staggering. The pictures, depicting reality, pose a hard argument against freshwater diversions.

Call me crazy, but it seems to me that once freshwater swamp is converted to saltwater marsh the effect is not reversible.

Of course, let's remember that freshwater, whether it builds land or not, still kills shrimp, crabs, oysters, speckled trout, and more.

Is that a desirable effect? I think not.

People have claimed that diversions like the one in West Bay have built land.

The land is miniscule compared to what Robbie Campo of Campo's Marina claims his colleague in the dredging business can accomplish, which is a staggering nine football fields a day.

Does Dredging Work?

Well...yes. In fact, it worked by accident.

In 2004, the Army Corps of Engineers was dredging out the MRGO (Mississippi River Gulf Outlet) to keep it navigable to ocean-going ships.

They pumped this material out of the MRGO and onto the opposite side of the rock jetty, where it piled up above the waterline and accidentally formed land.

The mud sat there as it was naturally populated by oyster grass, making it hardy against storm surge. This occurred on the south side of the MRGO, opposite of Gardner Island. See for yourself:

Island being built by a dredge in 2004.

Here the island is complete and has successfully survived Hurricane Katrina despite being devoid of oyster grass.

Here rests the island in 2010. It is definitely there and I can show it to you in person today.

If this accident is an example of the success found in dredging then what success lies in doing it with purpose?

Another great example of dredging is the ridge on the south side of the MRGO. It lies between the Spoil Canal and the MRGO itself. This ridge is made of material dredged from the MRGO.

If it is still there decades after its inception how much longer could it remain?

Clearly dredging is a successful and proven method. We can build back natural ridges such as the Hopedale Ridge to stave off storm surge!

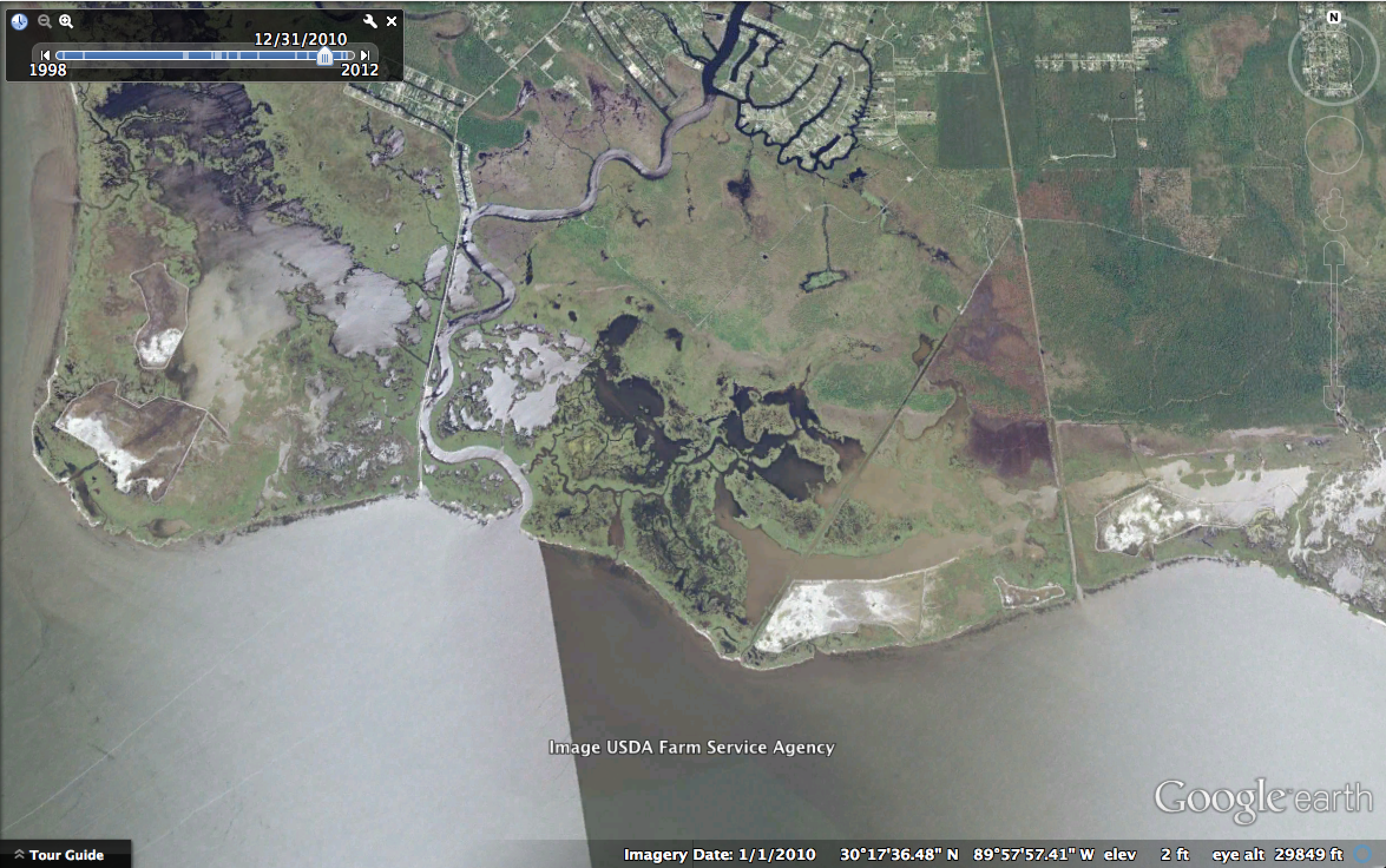

Here is some more successful dredging in Big Branch near Lacombe.

Big Branch 1999

Big Branch 2010

We know massive freshwater diversions kill our fisheries and the hardy saltwater marsh, so why do it? Why do it when we know dredging works?

These are all questions we should all be contemplating.

Quick Note

I wrote this article in May of 2013. Since then, now in August 2017, my opinion on river water has changed drastically.

I still believe dredging works and we should dredge our marsh back. No doubt!

But I share my observations since then, fishing across Louisiana's coast in a new article. CLICK HERE to read it.